The Common Core is on the minds of educators, parents, students, politicians, privateers, and publishing companies. I wanted to learn more about the CC, so I teamed up with a colleague to teach an in-service class in my district: “Connecting to the Common Core.” It begins on Nov.27 and I’ve been using my hurricane time to prepare.

The past two days I’ve read Writer’s Workshop for the Common Core, by Warren E. Combs, Ph.D. This book provides an education on the CC and emphatically praises the writing workshop as the most effective method for achieving its goals – it is exactly what I wanted to read. I don’t agree with all of Combs’ techniques, but he teaches readers a lot about the CC. Plus, his overall philosophy of writing education is outstanding (and just like mine!).

Combs (and I) believe that the writing workshop is by far the most effective and enjoyable way to teach students how to write. Sadly, language arts teachers just aren’t using the workshop model as designed and discussed by Nancie Atwell, Lucy Calkins, Donald Graves, etc. Thankfully, in the summer of 1994 – at the urging of my mother, a social studies teacher and principal – I attended the Long Island Writing Project Summer Institute. Combs is correct when he praises the National Writing Project as the #1 promoter of writing workshop.

The reality of establishing a workshop is intimidating. You can’t just open the doors and say, “Create Art!” Structure is mandatory in any workshop environment. I get most of my structure from only two handouts: “The Opening Day Packet” and “Goals & Deadlines.” Other structure comes from my "teacher-edit/final" system of evaluation, the notebook I use to track each students' projects, and my constant emphasis of due dates. I am not a fan of over-structure because I hate to be stifling. Combs is much more of a task-master and subscribes to his own theories of “The Writing Cycle.”

I agree in principle with “The Writing Cycle”: motivate your students to move writing through a process. However, I do not favor all the mechanisms behind the writing cycle – the logs, the self-evaluation rubrics, the self-assessment math (why are students figuring out their average number of words/sentence?), the proofreading triads, the Peer-Assisted Learning Systems (PALS – cute), and conversion charts. It’s way too much time and energy spent not writing. In the forward to this book, Ingrid Jones, a Professional Learning Specialist from Georgia, calls the Writing Cycle "writer's workshop with training wheels." Combs authored his book with fifth-graders in mind, which may account for his super-structure bias. I teach high school juniors and seniors and find that I don't need all these machinations to get students invested in their writing, putting pieces through a process, collaborating with each other, and producing outstanding work that is both personally satisfying and preparatory for the ELA, the SAT, the AP test, and the Common Core.

The Common Core is preposterously over-written, and both Combs and I could wade even deeper into its ocean of words: We could have pulled our quotes from the minutia found in the "Grade by Grade Standards."

The CC establishes ten Anchor Standards in Writing, ten in Reading Literature, ten in Reading for Information, six in Speaking & Listening, and six in Language. Right there that's 42 pieces of information for you to absorb and translate into teaching practice. But, each standard might have 3-6 details; let's call it 150 bits of information to learn per grade. Plus, you need to know what the grade before you was supposed to accomplish and what the grade after you is expected to accomplish - you have to see exactly where your class fits on the continuum. It adds up to an overwhelming task of reading, translating, and understanding hundreds and hundreds of goals, sub-goals, and sub-sub-goals.

The toughest part of the CC is trying to figure out what it says! That does not bode well, considering it’s a 79-page document whose purpose is to improve writing instruction. I won't even get into the litany of poor phrases and grammatical missteps that litter its charts, data analyses, and scientific explanations. I don't recommend using this labyrinthine document as a model in your classroom.

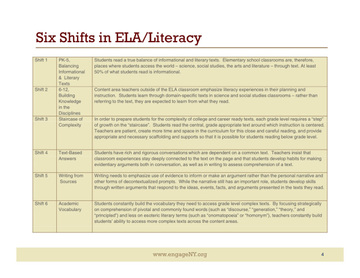

If you are struggling to understand something about the Common Core, trust me: Begin with the Shifts. When you feel like you’re ready to ascend, read the "College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards." At the peak of the CC's own "staircase of complexity" are the grade-by-grade breakdowns of expectations in the myriad categories.

After all, they are now being asked to fall in line with what I already do: teach students to analyze writing, construct convincing arguments, cite sources, do research, form opinions, and utilize the revision process. On the reading end, I’ve already been doing close readings, using nonfiction texts, encouraging high-level vocabulary, and connecting reading and writing throughout the disciplines. I do these things because they are emphasized in my training to be an AP teacher, which is the top of the writing-education pyramid. David Coleman's “top-down” philosophy - and much more! - is discussed in this excellent profile in The Atlantic.

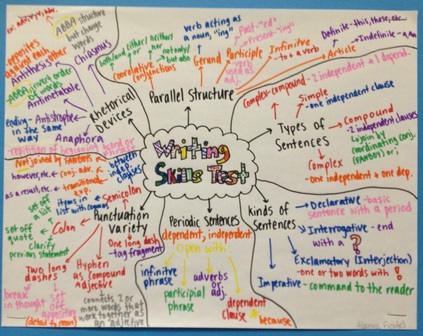

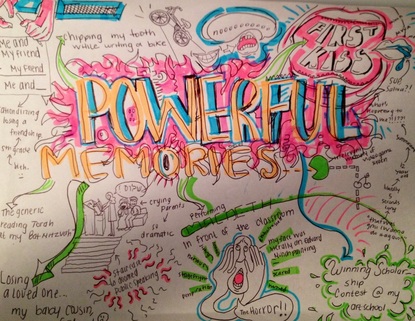

My favorite aspect of the Combs book is that it clearly states a truism I already knew: You can use the writing workshop to teach essay skills. For the most part, I have separated my AP class into two worlds: Writing Workshop to develop "authentic writing" like poetry, memoir, and mind maps; and Essay Writing that begins with the tasks given on the AP Language exam and breaks them down into lessons like designing a thesis, constructing a body paragraph, ICE'ing your quotes, and other traditions of the essay. No matter what world we're in, my classroom tone is set by the workshop atmosphere: enjoyable, social, embracing technology, and productive. Reading this book makes me realize that I can better combine those two worlds into one universe where students will choose if they work on a poem or an AP argument in today's class.

I should expand my students’ quarterly goals to include essays like “argument” or “style analysis” - in addition to poems, memoirs, and mind maps. I've been moving in this direction recently. For example, last year I included “poetic analysis” in my mini-lessons and on my "goals & deadlines." This year, I added an “outside reading reflection” for the first quarter for my AP classes. But, now I see a bigger picture where I can create options in both spheres: creative writing and essay writing.

1) Writing Workshop is awesome. Just like Nancie Atwell said it is.

2) Writing Workshop is awesome for developing essay skills and preparing students for a variety of local, state, and national tests. I concur with the Donald Graves quote presented by Combs: "You can take energy from Assessment."

3) Rubrics are terrific tools. You simply cannot be an effective writing teacher without using rubrics properly. I need to write a blog about my rubrics.

4) Teach with models: your own writing is best; former-student writing is second-best. My lessons always include one or two professional examples and 10-20 student-samples. I throw in my own writing all the time – for example, I will show this blog to my students and invite them to read and respond to it.

5) Set time limits and deadlines.

6) Students should find topics in their other classes.

7) Students can and should be taught to collaborate on writing.

8) You need to do lessons on sentences and paragraphs. Emphasize the sentence!

9) Write to be read. Publish.

10) You want to be able to say “My students are working harder than I am.”

11) It’s a lot of effort from you to edit and revise all this writing. Make no mistake, Combs writes, “Nancie Atwell worked her tail off.”

1) Combs is adamant that a teacher should write with his students. He even quotes Donald Graves: “The most powerful thing a teacher can say is ‘write with me.’” I emphatically disagree with both of them. When my head is down and I’m writing, I have no idea what my students are doing. I’m not comfortable with that. I like to move around my classroom and see who is doing what. Combs even says he went through a stage like me: “I used to prompt students to write and move around the room, trying to motivate the slower ones to get started; now I invite, sit down and write, and they all follow, each at his or her own pace.”

2) We definitely disagree about how much structure is required. But, I respect the man’s approach: it’s airtight. In my book I go in depth about balancing freedom & structure in my writing workshop. I prefer to do more coaching, encouraging, goal-setting, and motivating. I like to create options and see what students decide to do.

3) Combs – like Atwell – believes a class should be split into three blocks of time: mini-lesson, workshop, sharing session (author's chair). I tried this approach, but felt the sharing time disrupted students who were writing, collaborating, and creating. I think of class as two parts: mini-lesson and workshop time. Many of my classes are one part: just workshop time. I periodically lead my classes through exercises of sharing their writing and practicing their public speaking skills – in a great technique I learned from Jack Conklin called a whip – but it’s not built into the daily format.

4) The meaning of the word “portfolio.” Combs’ students keep a “working portfolio” of their materials. This sounds like it's over-loaded with all those self-assessments, peer-assessments, sentence-check charts, etc. I see portfolio as the final product of the course. In this way we greatly differ – Combs ends his book without even discussing a final project. In my view of the writing workshop, the final portfolio is a crucial element of success. The #1 long-term goal of the course is for students to produce portfolios. On the very first day of class, I tell my students, “You MUST have a portfolio to pass the class. You do it page by page, project by project, and in the end you will have this amazing book and you will be so proud of it you will never want to lose it.” I show them examples of all sorts of portfolios right on Day One. At the end of the year, EVERY student leaves the class with one.

a) Students do close readings of a few nonfiction texts. These need to be challenging pieces of writing for the grade level. “The biggest resistance [among teachers] will be whether they believe kids can handle the more complex, difficult texts,”

Coleman said. I definitely hear that resistance coming from teachers of younger grades. But, what can you do? Step up the level of reading expected in your classroom and do your best to coach students to understand it.

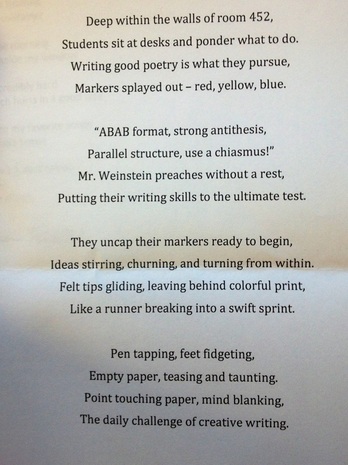

b) Students annotate the text. Now, this part is mentioned neither in the Common Core nor in the Combs book, but this is important in EVERY lesson: lead the students through an annotation of the text. It isn’t enough to just do a “close reading” – student must be told “write this definition…” or “circle that metaphor …” Use direct instructions to tell the students precisely what to do; teach them to be effective note-takers. For an added layer, have your students bring colored markers to class (mine do!) and take all their notes in full color. Taking notes in full color makes powerful connections to the brain, stresses creativity, and warms the atmosphere of an otherwise droll exercise.

c) Give the students a "standards-based writing prompt" that connects the reading to writing. Coleman loves to say that he wants students to “read like a detective and write like an investigative reporter.” Well, here’s where you have to cover the duality: teach your students how to analyze writing and how to write about writing. I had never viewed writing – and the teaching of writing – through this lens before I became an AP teacher. Now, it seems like the whole K-12 structure has to contribute to the detective/investigative reporter conceit.

d) Lead them through a writing workshop: mini-lessons and writing time. This, of course, is the tricky part. I suggest you enroll in a Summer Institute through The Writing Project. You could start by reading a book – or a library of them – about turning your classroom into a workshop. Since you’re on my blog, you may as well read mine first - especially if you teach older students. Combs recommends Denise Leograndis's Launching the Writing Workshop: A Step-by-Step Guide in Photographs.

e) Celebrate the finished product: read aloud, publish, portfolio.

You can also see the details in my sample lesson plan for aligning to the Common Core.

Everything I love most about teaching writing is derived from students creating powerful, important, original writing through lessons like Take Risks! Bleed on Paper! Find your Voice! and Pebbles!

Although the personal narrative is mentioned in the CC, Coleman has mocked its importance in our classrooms. He publicly stated that a boss would never tell an employee, “Johnson, I need a market analysis by Friday, but before that, I need a compelling account of your childhood.”

If Coleman could see just one of my students’ portfolios, he’d better understand the importance of creative writing.

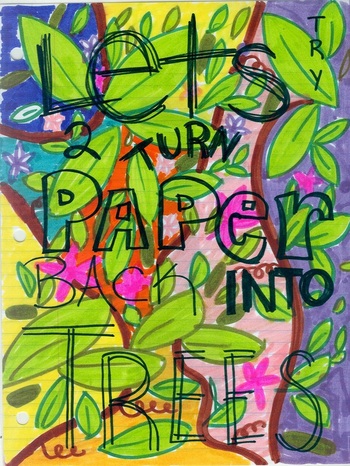

I now propose the Creative Core – which will be mandated concurrently with the Common Core. The Creative Core will demand that students write poetry and memoir and create artistic pieces like mind maps, cartoons, and visual poems.

In the Creative Core: Teachers must employ the Writing Workshop. Across the K-12 spectrum, class-time must be used more often to write than to talk about writing. "I know the writer's workshop can make peak-performing writers out of most students," Combs says. "Yet, the majority of teachers of writing remain untouched by it."

In the Creative Core: Students must write from the heart. They must have the freedom to choose their own topics, styles, and genres. They must produce careful art that has real meaning. They must be given time and space to discover their own voices, explore their own lives, and accomplish their own goals for writing. They must see that our websites, blogs, magazines, newspapers, and literature are not filled with Common Core essayists but with people who can express their own original ideas.

In the Creative Core: Every student, every grade, every year leaves with a portfolio, a stronger sense of self-worth, and a feeling of tremendous pride.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed